What is art anyway?

I’ve already shared here my position on generative artificial intelligence: I avoid using it due to ethical concerns and because I believe the human creative process adds unique value to my projects. However, I don’t completely dismiss AI as a tool—it can be useful for certain tasks.

The ethical issues surrounding generative AI—such as copyright infringement and its impact on creativity—often spark heated debates, especially among people working in creative industries like illustration, animation, and video game development. It’s common to hear the phrase “AI is not art” used as a rallying cry to argue that nothing produced by AI can truly be considered art.

Still, this statement becomes complicated when followed by the question: “What is art?”

To be clear, this text is not meant to undermine the struggle of working artists against big tech corporations. It’s evident that many large companies aim to devalue artistic labor and replace artists with AI in order to cut costs. In this context, the slogan “AI is not art” is useful to portray AI as soulless and lacking emotion tool, helping artists feel empowered and assert their value.

What I want to offer here, however, is a reflection on how this slogan might not hold up from a theoretical standpoint. The definition of art is complex and multilayered, and from certain perspectives, AI-generated pieces can be seen as art.

In the realm of contemporary art, for instance, generative AI can be embraced as a powerful tool. This field operates by its own set of rules — copyright infringement is often a secondary concern, and appropriation is considered a valid artistic strategy.

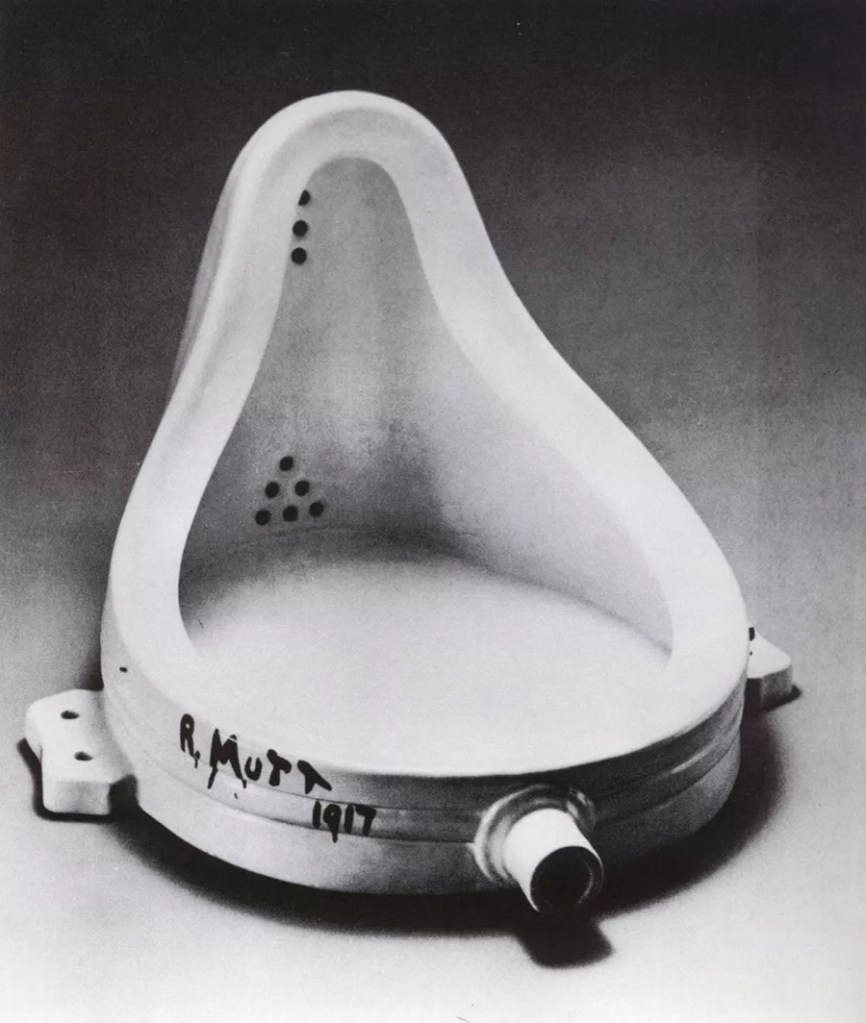

On April 9, 1917, Marcel Duchamp attempted to exhibit a urinal at the Society of Independent Artists’ salon in New York. The piece, titled Fountain and signed “R. Mutt,” had a clear purpose: to mock the established art world. At that time, art was defined by what galleries and museums deemed worthy of exhibition.

I believe Marcel Duchamp is the one who “killed” the classical notion of art and changed it forever. After him, anything could be considered art, as long as someone declared it so. Duchamp popularized the concept of the readymade: taking everyday objects from the world and presenting them in a gallery context as works of art.

In 1967, Brazilian artist Nelson Leirner submitted a stuffed pig inside a wooden crate to the 4th Modern Art Salon in Brasília. Around the pig’s neck, a ham was chained. He hadn’t raised the pig, cured the ham, or built the crate — everything was bought. He simply arranged the items and called it art.

Another art form that rose in prominence thanks to Duchamp is appropriation. This is when artists take something created by someone else, make small changes, and present it as their own.

In 1964, Andy Warhol recreated exact copies of commercial Brillo soap pad packaging and sold them to art collectors. The only difference was the material: Warhol used plywood, while the original boxes were made of cardboard.

In November 2024, Maurizio Cattelan sold his work Comedian — a fresh banana duct-taped to a gallery wall — for $6.2 million. The banana itself, however, could be bought outside the gallery from a street vendor for just 35 cents. But Cattelan’s concept transformed it into something else, something he could claim as art and justify at an exorbitant price.

These are just a few examples that show how modern and contemporary art often embrace appropriation and, to some extent, show little concern for copyright. But I want to highlight something even more striking: at some point in the evolution of contemporary art, the artist was no longer required to physically make the artwork. They could ask someone else—or even a machine—to create it.

In 2016, artists Sun Yuan and Peng Yu exhibited a robot designed to leak hydraulic fluid and continuously attempt to mop it back up. The fluid kept leaking, and the machine was stuck in a never-ending cycle, eventually deteriorating as it struggled to complete its task.

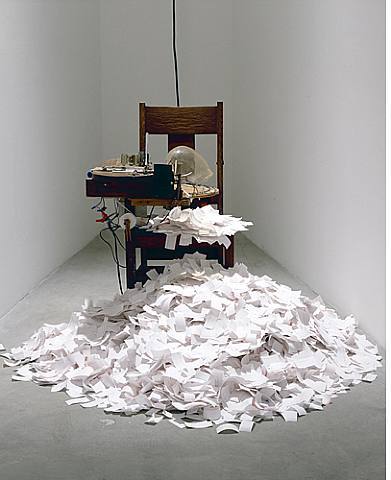

In 1993, Tim Hawkinson exhibited a chair outfitted with a machine that printed his name onto a strip of paper. Once the name was printed, a crude blade would cut it off, and the cycle would begin again. The entire process was automated.

Now, we have generative artificial intelligence. For over a century, modern and contemporary artists have explored the potential of readymades, appropriation, and machines — situations where the artist doesn’t directly create the work but still claims authorship. To me, using AI is simply a continuation of that trajectory in art history.

In 2022, Turkish artist Refik Anadol exhibited at MoMA Unsupervised, a work that is part of his Machine Hallucinations series. He used DCGAN, PGAN, and StyleGAN algorithms to process data from digital archives and public resources, generating constantly shifting visuals in real time. The audience was presented with something new and unexpected at every moment. A self-evolving artwork powered by AI.

With all these examples in mind, the question remains: What is art? And why shouldn’t AI-generated pieces be considered art, especially when contemporary art has long accepted pieces created by third parties rather than the artists themselves?

The definition of Art is not easy

When I studied at a Visual Arts college, the question “what is art?” followed me since my first year. And after the course conclusion, it was still an open question that not even the teachers know how to answer. I remember some classes where a teacher told us that “anything can be art, but art is not anything“. But he couldn’t explain any further. Another teacher said that this question is a big problem for the art field, and we tend to avoid questioning it to not get trapped in the rabbit hole (this same teacher said that the definition of music is much easier to achieve and Music students don’t need to worry with questions like “what is music?” because it’s somewhat solved, unlike Art).

I tried to bring some definitions of art to this text, but they’re not conclusive. Umberto Eco tried to answer this question on his book “The definition of Art”. Leonardo da Vinci also gave his 2 cents on this matter by saying that there is a difference between the artist and the artisan on his text “Trattato della Pittura”. You can dig every art text from artists and researchers, and everyone will bring a different answer. Honestly, it’s such a headache.

What makes AI-generated art so controversial is the fact that it is created by a machine. So, allow me to introduce another machine product that is now accepted as art: photography. In fact, photography took many decades to be considered art due to various debates, and was only recognized as such in the 1960s, being later acclaimed by art theorists like Susan Sontag and Roland Barthes.

That’s why the argument that AI can’t be art is so weak. We still don’t have a final definition about art. This is an open question for more than 100 years, if you think about the vanguard artists and the split of art into many other fields created to sustain a great demand for consumption – design, craft, advertisement – fields that in the past belonged to the artists.

AI “art”?

The issue of artificial intelligence is not that if it can make art (real art!) or not. It’s more like an ethical concern, not a definition problem.

Some people may say, “what makes a piece of art so valuable is the time that the artist had to research, plan, design and finally make their art. Even in the examples above, artists needed some level of effort and time to make their works – even those cases where they delegated it to someone else to do” or “there is also some kind of beauty in the process of learning a skill and applying it into a drawing or painting, for example.” But art is not defined by those terms. Contemporary art doesn’t even consider “beauty” a criterion for existence – in fact, art can be subversive nowadays. As so is AI.