Why does this spark so much debate?

It’s no secret that nudity makes many people uncomfortable. Yet even as it remains taboo, the naked body is also an object of desire. Whether it sparks outrage in mainstream media, however, depends on countless factors, and often on who stands to benefit from the controversy.

The fact is, nudity has been part of art since the beginning — prehistoric cave paintings and carvings already featured figures with no covering. Sometimes, this nakedness held symbolic meaning: depictions of men with exaggerated phallus or women with full breasts may have represented fertility rituals or spiritual ideals.

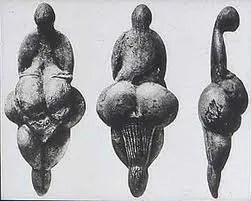

Venus of Lespugue

But nudity in prehistory also had a more literal dimension—it may have been a way of representing oneself. Some studies suggest that many Paleolithic “Venus” figurines, such as the ones from Willendorf and Lespugue, were likely carved by women. The angle and perspective of the figures only make sense if viewed by someone looking down at their own body, which supports the idea that these pieces are self-representations.

Poseidon of Artemision

In Ancient Greece, the nude body — especially the male body — took on a new meaning. It became a symbol of strength, balance, and rationality. The fact that many sculptures depict men with small, soft phallus reflects this ideal — a large, erect genitalia was seen as vulgar and savage, a sign that a man hadn’t mastered his base instincts.

With the rise of Christianity in the West, nudity in art was gradually erased during the Middle Ages, as it became associated with Original Sin. But during the Renaissance, classical ideals returned — and so did the nude, though with some key differences: female nudity became more objectified and catered primarily to the male gaze.

It’s important to pause here and clarify two concepts. In art, there’s a difference between being naked and being nude. A naked body is free, unashamed, with nothing to hide. A nude body, on the other hand, is on display — it’s an object meant to be looked at.

“To be naked is to be oneself. To be nude is to be seen naked by others and yet not recognized for oneself. A naked body has to be seen as an object in order to become a nude. (…) Nakedness reveals itself. Nudity is placed on display. To be naked is to be without disguise (…) The nude is condemned to never being naked. Nudity is a form of dress.”

(John Berger, Ways of Seeing)

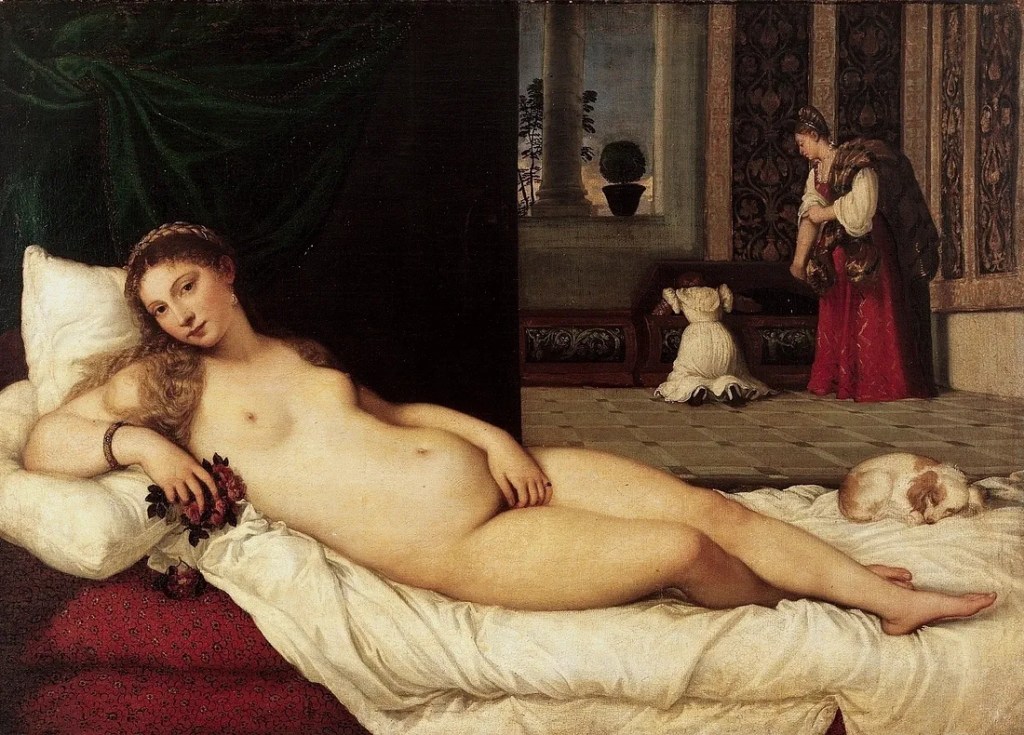

“Venus of Urbino”, by Ticiano Vecelli (1538)

Renaissance paintings of female nudes often show the woman facing the viewer, her body fully revealed, her expression calm, passive, and demure. She’s always young and alone — and if there are others in the scene, they often ignore her or remain in the background. Works like the Venus of Urbino were almost always commissioned by men and meant for their private enjoyment.

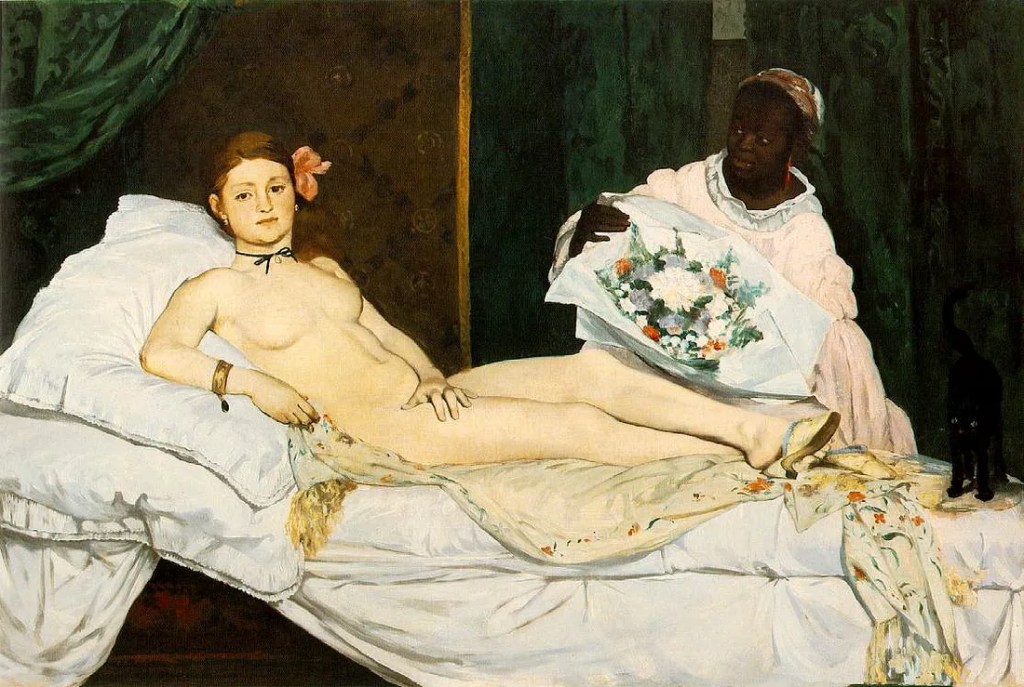

“Olympia”, by Édouard Manet (1863)

In the Modernist period, this depiction of the nude began to be questioned. Artists also changed how the body was portrayed. A prime example is Olympia, which shows a woman returning the viewer’s gaze with boldness rather than submission. Her left hand presses firmly against her right thigh, guarding her genitals in a confrontational way — unlike earlier depictions, where Venus’s hand rests gently, almost carelessly, over her sex, as if unaware of the many eyes that might be watching, and desiring her. Olympia goes even further: her body appears intentionally unglamorous. The ribbon around her neck, the flower in her hair, and the slippers on her feet all suggest she’s a sex worker, completely at odds with the fantasy of the “ideal woman.”

From the 20th-century avant-garde movements onward, many performance artists began to explore the naked body in non-objectifying ways. Men and women alike began to appear “without disguise” — sometimes as a form of self-discovery, sometimes to challenge societal norms about nudity. This approach continues today, often tied to broader contemporary conversations.

“DNA de DAN” by Maikon K. Photo by Victor Takayama

Even now, people often confuse nudity with being naked. We regularly see nude bodies on magazine covers or in beer ads, and few people raise an eyebrow. But when a truly naked body appears — a body that isn’t sexualized or posed — it tends to spark outrage. We accept the body as a commodity but recoil when it’s just a body, unhidden and unadorned.

Free, unfiltered bodies are threatening to closed minds.

Suggested reading:

O corpo não pornográfico existe

LINS, Daniel Soares; GADELHA, Sylvio. Nietzsche e Deleuze: que pode o corpo. ed. Nova Fronteira. Rio de Janeiro, 2002.

Suggested videos:

Miru Kim: My underground art explorations

Perfoda-se — Um Documentário Sobre Performance Arte